A CONTINUATION AND UPDATE

BY DOROTHY COCIU

Author’s Note: Part 1 of this article was printed in the October 2021 issue of California Broker. This is Part 2 and includes updates from the September 30, 2021 rules on the Independent Dispute Resolution Process of the No Surprises Act.

Independent Dispute Resolution (IDR) Process

Most of us have experienced the unsettling nervousness when an outsider, someone who doesn’t know a thing about you, determines your fate. We’ve seen it in divorce mediation, child custody matters and business matters. All we can do is present our documentation or orally present our argument up front, and then the other side does the same, with vastly differing conclusions and perspectives. But somehow, we must find a way to make it work; to meet in the middle or find a resolution. And sometimes, as we all have experienced, the emotions are overwhelming, and no compromise seems acceptable.

When money is involved, it becomes not only emotional, but financially devastating in many circumstances. Now combine the financial impact to you or your company with the human resources side of wanting to do the best you can for your employees and their dependents covered under your health plan. To employers sponsoring a health plan and wanting to do the right thing for their covered participants, it can become overwhelming.

Your client’s employee did the right thing. They followed the health plan’s rules and they went to an in-network facility for care, only to receive later an unwanted “surprise medical bill” from a non-network assistant surgeon, as well as one from the anesthesiologist. The total of these bills was over $25,000, which the employee simply does not have the money for. The human resources director (let’s call her Judy) sat there fighting to hold back tears as this employee (let’s call this employee Pam, who is a wife and mother, and handles all of the insurance and health care related matters of their family) sat across from her desk and showed Judy the stack of medical bills that she was instructed to pay. As Pam explained,with the kids’ college expenses and the cost of rent, gas for the car, groceries and everything else going up, there is no way she can pay. Pam, who is a valuable employee, was hysterical, asking why this happened when they took great care to go to the PPO facility that she was told to go to. Pam and her husband planned for this surgery. They saved the money for their co-pays or coinsurance, plus any deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs that might occur. Now Pam is accusing her employer of having a horrible health plan, when in reality it pays 90% of in-network costs, with a low annual deductible of only $250 and affordable co-pays and out-of-pocket maximum for all services.

Surprise billing is something none of us wants to see, yet it happens all too often. The No Surprises Act attempts to stop some of the most egregious balance billing practices of providers in non-network situations by limiting the amount of the bill to the amount that would have been payable under an in-network arrangement. Protections apply primarily to emergency services, non-emergency services delivered by out-of-network providers at an in-network facility, and out-of-network (OON) air ambulance services. I addressed the No Surprises Act in detail in the article entitled: “CAA’s No Surprises Act IFRs Spark Administrative Questions and Industry Concerns While Awaiting Further Guidance,” published in the September/October, 2021 issue of The Statement, and the October, 2021 issue (part 1) of California Broker Magazine. If you haven’t read that article yet, and are confused on some of the things I state in this article, I suggest you go back and read those articles first… Then this one will make much more sense!

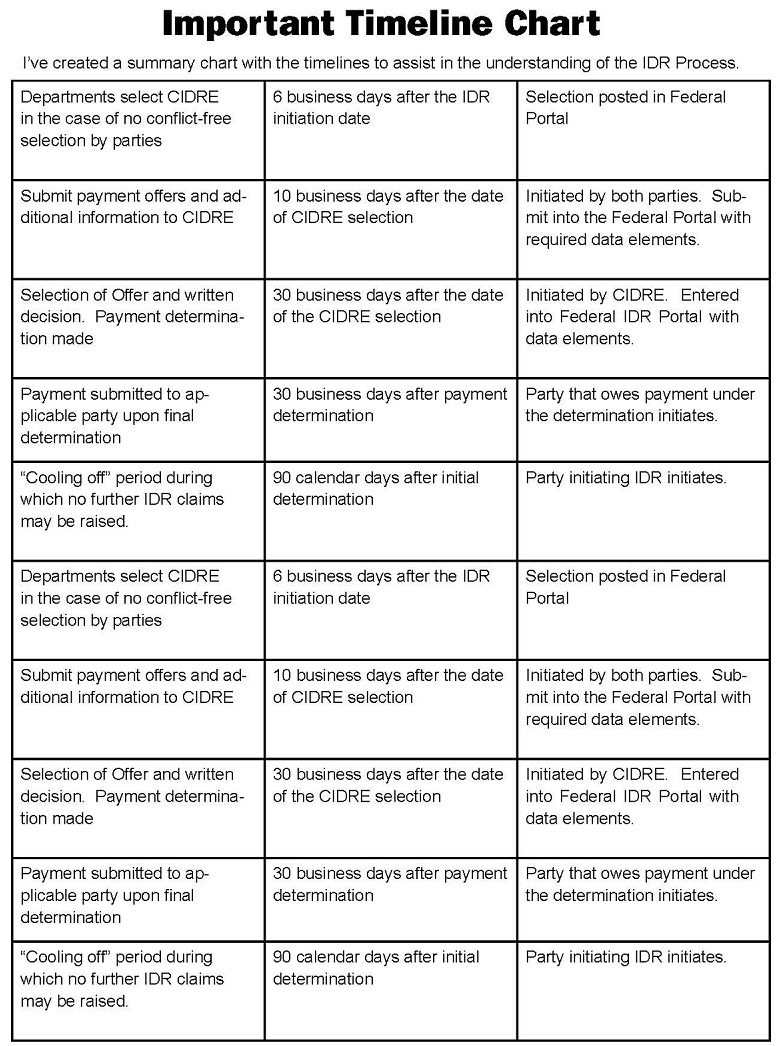

In the last Cal Broker article, I wrote briefly about the Independent Dispute Resolution Process (IDR) that will be required under the No Surprises Act, but we were awaiting rules on how that process would work. Now, we have those rules, as they were released on September 30, 2021, in the No Surprises Act’s second interim final rule.

New Federal Portal to Resolve Payment Disputes

The new rules outlined a new resolution process that OON providers, facilities, providers of air ambulance services, plans and issuers in the group and individual markets may use to determine the OON rate for applicable items or services after an unsuccessful open negotiation. The September 30 rules (published in the Federal Register on October 7, 2021) outline the federal independent dispute resolution process, good faith estimate requirements for uninsured

(or self-pay) individuals, patient-provider dispute resolution process for uninsured (or self-pay) individuals, and external review provisions of the No Surprises Act. The most prevalent part of the release of new rules on the IDR included the announcement of the newly created federal portal website where providers and plans will submit their payment disputes, which can be found at: https://www.cms.gov/nosurprises/consumer-protections/Payment-disagreements. The full website contents can be found at: https://www.cms.gov/nosurprises. Included in that portal is an application process for entities to become a certified independent dispute resolution entity, or an Arbiter for the process.

The new federal portal is not yet completed, but is a work in process, and all indications to date are that the portal, once fully operational, should ease the independent dispute resolution process. Because it is a complicated process, I will attempt to walk you through how it will work.

I recently interviewed Ryan Work, Vice President, Government Affairs and Chris Condeluci, Washington Legal Counsel for the Self Insurance Institute of America (SIIA) for my podcast, Benefits Executive Roundtable. This podcast aired on November 2, 2021. In that interview, I asked Ryan and Chris some important questions and gained some valuable opinions on how the IDR process will work. I’ll refer to some of their comments throughout this article, as I think they will help you to better understand the process.

When asked about the creation of the federal portal and if they thought it would be helpful in the IDR process, Ryan commented: “The fact that the federal agencies have moved quickly to implement this is pretty amazing to me… I think everyone should bookmark that page…”

Chris also seemed to be happy with the new CMS portal for the IDR process. “I do think that it will be very helpful, and I do think that the plans, service providers and everybody in this process should indeed bookmark that page, because it will be a living, breathing entity or tool… There will be important information relating to CIDREs, all information on time periods, etc. So, it’s advisable to keep looking back at that federal portal for informational purposes.”

I also discussed these new rules with Colleen Dempewolf, Director, Strategic Product Development, MultiPlan, who we will hear from later in this article. MultiPlan is a national PPO network which also owns HS Technologies, a Referenced-Based Pricing vendor. I previously interviewed her and Ryan Day, President of HS Technologies, for an earlier No Surprises Act podcast from both the Benefits Executive Roundtable and CAHU.

Before initiating the federal independent dispute resolution process, disputing parties, according to CMS, must initiate a 30-day “open negotiation” period to determine a payment rate. In the case of a failed open negotiation period, either party may initiate the federal independent dispute resolution process. The parties may then jointly select a certified independent dispute entity (or CIDRE – a new industry acronym coined first by Ryan and Chris from SIIA to the best of my knowledge) to resolve the dispute. The CIDRE and personnel of the entity assigned to the case must attest that they have no conflicts of interest with either party. If the parties cannot jointly select a CIDRE or if the CIDRE has a conflict of interest, the Federal Departments will select a CIDRE for them.

The No Surprises Act requires the Departments to establish a process for receiving complaints regarding potential violations of the law by providers and insurers.

After a CIDRE is selected, the parties will submit their offers for payment, along with supporting documentation, into the federal portal. The CIDRE will then issue a binding determination selecting one of the parties’ offers as the OON payment amount. Both parties must pay an administrative fee ($50 each for 2022), and the non-prevailing party is responsible for the CIDRE entity fee for the use in this process. The CIDRE total compensation is discussed later in this article.

Before I get too deep into the IDR process, I want to first make mention that not all parties seem to be happy with the IDR rules in the No Surprises Act IFR, Part 2. I asked Ryan Work about how the response from the provider community has been on the IDR process.

“The best word I can use to describe it was ‘enraged,’ by the arbitration rules. I think one of the best quotes from one of the hospital associations was that this was a ‘gift to the insurers on a silver platter,’ which I disagree with, but I think that everything else that was done with Surprise Billing and the politics of it, and honestly the tens of millions of dollars spent by the hospitals against this in the first place, that the policy that came out of the IFR was well deserved.” If this process sounds simple so far, let me tell you… It’s not. Let me get into more of the details.

Step One: Initial Payment or Denial of payment.

Once a plan receives a claim for an OON service, the plan has 30 days to either choose to send the provider and initial payment or a denial of the payment. The provider and payer may negotiate with each other on a final payment amount over a 30-business day period. If they agree on an amount within this 30-day period, the process ends. The claim is finalized, and all is well. If, however, they cannot agree on a payment amount within the 30-business day period, either party can enter into the federally-developed arbitration system (IDR process) within four business days after the end of the Open Negotiation Period. If this occurs, the “certified arbiter” will make a final determination within 30 business days after being selected to consider the dispute.

The No Surprises Act attempts to stop some of the most egregious balance billing practices of providers in non-network situations by limiting the amount of the bill to the amount that would have been payable under an in-network arrangement.

The Open Negotiation Period:

The 30-business day Open Negotiation Period does not begin until the provider receives the initial payment, or the denial of payment, and the provider sends an “Open Negotiation Notice” to the plan indicating that the provider wants to negotiate. If this happens, it must be sent within the 30-business day period. This notice, which may be sent electronically to the plan, marks the date that the 30-business day period begins for the Open Negotiation Period. The initial payment or denial of payment that is sent to the provider must include a written statement that informs the other party that the Open Negotiation Period has begun and must include the appropriate contact information to send the Notice.

It is possible, and somewhat probable, that the majority of the claims will be settled within the first 30-business days, during the Open Negotiation Period. “I think the federal agencies have written these rules to give as many options in the open negotiation period as possible and avoid arbitration. I also think that reaching a settlement in open negotiation will probably depend on the amount of the service [cost]…,” stated Ryan. “I think price strategy by the plans and providers will play It depends on where the savings are.”

Colleen Dempewolf had similar thoughts: “The departments have written the No Surprises

Act to incent providers and payors to come to agreement rather than employ an arbitrator, so we expect the arbitration volume to be well below the volume of claims negotiated. However, the new reimbursement process will have a significant impact on both provider revenues and payor medical cost, so we fully expect that there will be claims where the arguments for arbitrating are compelling for either party.”

For the most part, it seems as though many providers may want to try to settle in the Open Negotiation Period, rather than to risk a lower payment in the arbitration process, but we shall see.

The Arbitration Process: It begins with either party initiating the IDR process within four business days after the Open Negotiation Process ends. Keep in mind, the 30-business day Open Negotiation Period must be exhausted before the arbitration or IDR process can begin. It starts

by the initiating party sending a “Notice of IDR Initiation” to the non-initiating party. This notice MUST be sent electronically to the plan and the federal Departments. The date of receipt in the Federal IDR portal will begin the arbitration/IDR process. Once the arbitration/IDR process begins, the parties must agree on a CIDRE within three days. If the parties cannot agree, the Federal Departments will assign a CIDRE within six days.

I want to comment on this part of the process before we go any further. The Federal Departments have reported that they only expect to have approved 50 to 75 arbiters to be certified by the effective date of January 1, 2022. CMS is actively looking for parties to apply to become a dispute resolution organization. It’s now November… The effective date is January 1, 2022… That is not a lot of arbiters to act as the deciding party, particularly in the first six months or so of this process. I can’t imagine that the providers are happy with the No Surprises Act, as I mentioned above, so I am guessing that they will not want to accept the initial payment offered for the higher cost claims, such as hospital stays and high cost air ambulance services, and will likely try to negotiate those in the first 30 days, in the hopes of receiving more revenue per claim.

I will discuss this further later in this article, but I wanted to point out that we will likely begin with very few approved arbiters to do a lot of claim settlements.

When I asked Colleen Dempewolf about the number of arbiters that will be available for the IDR process, she shared her thoughts. “The time available for CMS to make a reasonable pool of certified IDR entities available is very short and it is difficult to tell how many would be in place, trained and operational at the start of the year. Of course, there is a considerable lag between the date services are rendered and the time it would be in the IDR process. In addition, we don’t know how many arbitrators would be available from the 50-75 entities that SIIA is expecting. If the supply can’t support the demand, we expect CMS will have to accommodate the resulting inability of payors and providers to comply with the process requirements.”

Choosing An Arbiter: If the initiating party and the non-initiating party should come to an agreement on the CIDRE, a notice must be sent to the Federal Departments though the Federal Portal that includes the following:

- The CIDRE Name and Registration Number

- An attestation by both parties that the CIDRE does not have a conflict of interest (or by the initiating party if the other party has not responded)

- The attestation must be submitted based on conducting a conflicts of interest verification by using information available, or by using information accessible by using reasonable means

- Providers and payers can petition the Federal Departments and argue that a particular entity that is seeking to become a “certified arbiter” should be denied a certification Parties can request to the Federal Departments that an existing certified arbiter’s certification should be revoked

In summary of the latter, the rule provides a process by which members of the public, including providers, facilities, providers of air ambulance services, and plans or issuers, can petition for the denial or revocation of a certification of an independent dispute resolution entity.

Arbiter Certification: When choosing an arbiter, there can be no conflicts of interest on either side. The arbiter cannot be an employee or former employee of a disputing party within the past year or a former employee of the Federal Government within a year of the time which the employee left the employment of the government. They cannot have a financial, professional, or family relationship with either party. In addition, the arbiter cannot be owned, either directly or indirectly, by an insurance carrier or medical provider. The arbiter also cannot be an affiliate/subsidiary of a professional trade association for the group health plan, carrier, or providers.

The arbiter needs to have sufficient expertise in the arbitration and claims administration of health care services, managed care, billing, coding, medical and the law. They must also have expertise which is considered sufficient in the field of medicine, especially where the payment determination depends on the patient acuity or the complexity of the medical procedure, or the level of training, expertise, experience and quality and outcome measurements of the provider or facility that furnished the medical service or services. Arbiters are required to maintain current accreditation from a nationally recognized and relevant accreditation organization, such as URAC, or employees must have requisite arbitration and topical training. So, the bottom line is, not everyone can apply and be accepted as a CIDRE.

The Submission of Offers: When submitting “offers” of payment, both parties must submit an “offer” for the OON payment in dollars and a percentage of the QPA represented by that dollar amount, within 10 business days of the CIDRE selection. Providers must provide the size of their practice by the number of employees that they employ, and whether the provider is a specialty provider. Health plans must provide their coverage area, QPA geographic area, and must state whether the plan is fully insured or self-insured. Health plans must also state the QPA for the applicable year of the claim dispute.

Arbitration/IDR Payment Factors/QPA: It’s important to state that the QPA, or the median in-network rate, is the primary factor in a final payment determination. The CIDRE must assume the QPA represents a reasonable market-based payment. The CIDRE must begin with the presumption that the QPA is the appropriate OON amount. The CIDRE must also consider the QPA, or the offer closest to it, as the final payment amount. Keep in mind that it is NOT the role of the CIDRE to determine whether the QPA was calculated correctly. Their job is to simply consider the information that is submitted by both parties and consider whether any “additional criteria” is already reflected in the underlying QPA, to assure there will be no “double-dipping.” The CIDRE can also consider whether information that shows efforts to alter the service codes have occurred, which might result in “up-coding” or “down-coding” billed amounts. Down-coding may show that the QPA is artificially low, for example.

However, the CIDRE is permitted to consider “additional criteria” that may lead to a higher payment amount than the QPA. Such additional criteria includes the level of training, experience and quality of care, as well as the outcome measurements; the acuity of the patient and complexity of services, a good faith effort to enter the network by the health plan and provider, market share held by the provider or facility in the region; teaching status, case mix, scope of service of facility; or contracted rates over the prior four years. This additional criteria could cause the payment rates

to increase for providers, so it’s likely that providers will include as much of this as possible in their submissions.

Before initiating the federal independent dispute resolution process, disputing parties, according to CMS, must initiate a 30-day “open negotiation” period to determine a payment rate.

Part 2 rules made it clear that the IDR entities will not give equal weight to both the QPA and additional factors, and that the IDR entities will be instructed to “select the offer closest to the QPA” unless the certified IDR entity determines that credible information submitted by either party is materially different from the appropriate out-of-network rate.

If the “credible information” demonstrates that the QPA is “materially different” than what an appropriate payment for the OON service should be, the CIDRE may choose a higher amount.

I asked Colleen Dempewolf of MultiPlan about the IDR entities being instructed to select the offer closest to the QPA unless the CIDRE can determine that credible information submitted by either party clearly demonstrates that the QPA is materially different from the appropriate OON rate.

“Most observers, including MultiPlan, see this rule as favoring the payor. Providers most certainly would prefer that more weight be given to training, acuity, etc. in selecting between the final offers. That said, the rule doesn’t prohibit them from arguing these points – it just makes

it harder to do so because they must show evidence, not just that these considerations are applicable to the claim, but also that the QPA doesn’t sufficiently take them into account. Effectively, with QPA holding so much weight at arbitration, it’s possible providers will be less inclined to take claims to arbitration and more inclined to negotiate a settlement. Of course, this depends on how reasonable the provider views the payor to be.”

Once a plan receives a claim for an OON service, the plan has 30 days to either choose to send the provider and initial payment or a denial of the payment.

I also asked Ryan Work about those additional factors that may warrant higher payment amounts, and how these will impact self-funded health plans. “For this final amount that potentially a self-insured plan is submitting as part of the arbitration process, it behooves the plan to consider these other factors… And put those into the payment amounts, so they are close to that, and the arbiter sees that and understands that they are included. That’s one of the differences between the QPA and a final payment amount that is submitted in the arbitration process.”

There are many factors that the CIDRE may not take into account, including a provider’s usual and customary charges, a provider’s “billed charges,” rates paid by any public payer payment or reimbursement rates such as Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP or TRICARE, or past arbitration decisions as a precedent. That is not to say that a plan using referenced-based pricing, for example, cannot use some form of rating above Medicare rates (such as 150% of Medicare). The interim final rule clarifies that the CIDRE cannot consider which “offer” is closest to 150% of Medicare; however,

the Federal Departments noted that in-network contracted rates are frequently based off a percentage of Medicare rates. Because such basis of the Qualified Payment Amount is the in-network contracted rates, if the QPA is calculated using a percentage of Medicare, then the CIDRE can take into account this percentage of Medicare value. In this case, the percentage of Medicare value represents the QPA and not a particular offer from the disputing parties.

To clarify this concept for RBP plans, I asked Chris Caladuci to break it down. “The federal agencies specifically said of payer and provider… your offer can’t be 150% of Medicare. But what an arbiter is allowed to do when we’re dealing with a value based on the percentage of Medicare, is that if the percentage of Medicare value is the basis for the QPA, this median in-network rate then, by definition, the CIDRE can take into account the percentage of Medicare, because the CIDRE has to look at the QPA, the median network rate, as the primary factor.”

Chris continued: “You can’t come in with a 150% of Medicare offer, but if the QPA is based on a percentage of Medicare, then that can be taken into account by a CIDRE.”

Colleen Dempewolf had this to say on the matter: “The Act does not say that the initial payment cannot be based on these amounts, only that at arbitration the IDR entity may not consider these amounts as justifying a final offer. An RBP program using a percentage of Medicare to price claims where there is no network would likely consider the default Medicare-based price to be the QPA for these claims, and can make any reasonable arguments for an offer that speaks to that Medicare-based price. What they can’t do is justify it as an appropriate payment because it is over the amount Medicare would pay for the service in that geography.”

In our discussion, Ryan Work also had some helpful comments on RBP plans and use of Medicare Rates in the QPA determination. “There was an important footnote in the 2nd IFR. Basically, if you use a multiple of Medicare to determine the QPA for your in-network rates, you can continue to do that, and the arbiter must consider that as the QPA amount. To me, that footnote in and of itself is the Agencies’ trying to understand and bring in RBP plans into the QPA when it comes to an OON emergency care event.”

Final Payment Determination: The parties may continue to negotiate after the IDR process begins. If an agreement is reached, the initiating party must inform the Federal Departments within three business days after agreement, and the final payment must be made no later than 30 business days after they have reached agreement. If the parties cannot agree on a payment rate, the CIDRE must make a final payment determination 30 business days after its selection. The Federal Departments may extend the 30-business day period on a case-by-case basis if the extension is necessary to address delays due to matters beyond the control of the parties or for “good cause.”

The determination of the IDR entity is binding on the parties and is not subject to judicial review, except in narrow circumstances, such as fraud.

As an attorney, I asked Chris Caladuci about the binding arbitration. He responded: “The arbiter’s decision cannot be challenged in court, unless there is fraud or misrepresentation that can be proven. Otherwise, the arbiter’s decision, the CIDRE’s decision, is binding on both parties and final.”

Ryan Work also commented on this, stating, “That arbitration determination for that case does not have precedent for the future. So, the arbiter or a similar case, or a code two months from now can’t go back into the files and look at another arbiter’s decision on that. It’s not a precedent. It’s basically almost like blinders from one case to another.”

As stated in my last article, the IDR process will use a “Baseball-Style” Arbitration process, meaning that the CIDRE is required to pick one of the two “offers” which is closest to the QPA. The amount of the offers will determine that amount. It could be that the QPA itself is the final amount, or it may be higher or lower than the QPA, depending on the offers submitted.

I asked Chris Caladuci to better explain the “baseball arbitration, for anyone not as familiar with it. “Baseball arbitration is, in short, the plan comes in with an offer, the provider comes in with an offer. The CIDRE must pick either the plan’s offer or the provider’s offer.

The CIDRE does not pick something in-between. That is what baseball arbitration is…. You pick an offer that is submitted by the parties.” The arbiter cannot split the difference. The amount closest to the QPA should be the final amount of payment, unless the additional factors come into play. The cost of the arbitration is paid by the losing party.

Keep in mind, as mentioned above, if the provider submitted “credible information” showing a “material difference” between the QPA and the value of the service, the arbiter could choose the provider’s offer, even if that offer is further from the QPA than the plan’s offer. Once this determination is made, the CIDRE must provide the underlying rationale in a written decision to the portal submitted to both parties and the Federal Departments.

It may take a year or more to make this process understood by everyone. It may not be smooth in the beginning. With this and the claims process itself having to make adjustments due to the No Surprises Act, I am guessing it will be at least a year before it’s running well. I think the first six months will be rocky for everyone, particularly if they don’t have enough CIDREs. They could rush the decision-making to move onto the next case, or there could be a backlog. We’ll have to see what happens as this rolls out in January.

Cost of the Arbitration/IDR Process: To begin the process, each party must pay a non-refundable $50 fee when the CIDRE is selected. The CIDRE is required to post their charged fees in the Federal Portal. The IDR fee range at this time, according to guidance, is expected to be in the $200 to $500 range for single determinations and $268-$670 for batched determinations. Both parties must then pay the CIDRE fee when they submit their respective offers. Within 30 business days of making the final determination, the CIDRE must refund the prevailing party’s fee payment. The losing party does not get a refund. So if the fee is $500, both parties submit $500… The losing party pays the $500 fee, and the winning party gets their $500 refunded. The loser pays fees; winner does not in baseball-style arbitration.

Cooling Off Period: The initiating party may not submit a subsequent dispute with the same other party for the same or similar item or service with 90-calendar days. In this situation, a plan can’t constantly be filing for IDR for the surprise billing process with the same provider.

No one wants to be the HR Director we called Judy. Even more, no one wants to be in the position that our employee, who we called Pam, was in when she sat across from Judy’s desk.

The stress of the past 18 months+ was more than enough stress for all of us. The last thing we need is to be hit with Surprise Medical Bills. Hopefully, these new rules will at least reduce considerably the number and amounts of large surprise medical bills; at least for those situations stated in the No Surprises Act.

Facility/Provider Notices

There are required notices for Facilities and Providers. The first is the Patient Consent for Out-of-Network Care, which requires providers and facilities to provide a notice to a patient regarding potential out-of-network care. The patient must consent to such out-of-network care and any additional costs that may be incurred. However, there are exceptions. A patient is not required to sign the form and should not sign it if they didn’t have a choice of health care providers when they received care (i.e. a forced provider).

There is also a Public Notice requirement for facilities and providers to post a one-page notice on a public website. The Model Disclosure Notice Regarding Patient Protection Against Surprise Billing is required under Section 2799B-3 of the Public Service Act. A provider must make publicly available such notice by posting it on a public website of the provider or facility, and provide a one-page notice that includes information in a clear and understandable language on 1) the restrictions on providers and facilities regarding balance billing in certain circumstances, 2) any applicable state law protections against balance billing, and 3) information on contacting appropriate state and federal agencies in the case that an individual believes that a provider or facility has violated the restrictions against balance billing.

The Model Notices can be found at cms.gov.

Health insurance and Health Plan Notice:

Health insurers and Health Plans must provide a notice to individuals about their rights under the No Surprises Act. There is a Model Notice available on the DOL website (although it has been on and off the site a few times since I started researching for this article, so they could be updating it). The notice must be posted on the plan’s website and be included on each EOB for an item or service covered by the No Surprises Act. Although TPAs may assist in preparing this notice for self-funded plans, the plan sponsor has the ultimate responsibility for compliance.Plan participants can expect that their EOBs will become quite thick when they receive them in the mail… Hence, more administrative/postage costs also.

I asked Marilyn Monahan if a plan is self-insured and uses a TPA, is there coordination that is needed between the plan sponsors and the TPA about the notices that are included in the EOB? Does (or should) the Plan Sponsor notices be the same, consistent notices? I expressed to her my fear that the plan notice may differ from the TPA’s notice, causing some confusion and possible liability.

Marilyn clarified: “The IFR contains new notice and posting requirements. For example, health care providers must provide certain notices to the plan or issuer, and additional notices to patients. Another notice and posting requirement applies to plans and issuers; plans/issuers must post and provide certain notices to participants, including a notice that should accompany explanations of benefits (EOB). Regulations have not yet been issued on the mandate applicable to plans/issuers. In the meantime, the Departments expect plans/issuers to comply using a ‘good faith, reasonable interpretation’ of the CAA. Also in the meantime, a model notice has been issued which may be used by plans/issuers. Ultimately, in the case of a self-funded plan, the responsibility for issuing compliant notices rests with the plan, and not the TPA. The employer should therefore work with its TPA to ensure that compliant notices are prepared and distributed, and that all legal requirements are satisfied.”

The CIDRE can also consider whether information that shows efforts to alter the service codes have occurred, which might result in “up-coding” or “down-coding” billed amounts.

No Surprises Act Impact on Self-Funded Health Plans Using Reference-Based Pricing

The No Surprises Act’s limitation on balance billing for services provided in an “in-network” facility by an out-of-network provider is likely to be quite problematic for self-funded plans that use Reference-Based Pricing as their financing method, in place of a PPO network. Because there is no network, and all claims are generally paid at a reference-based rate (most commonly a percentage above known Medicare Rates, such as 150% or 200% of Medicare), such self-funded health plans and their RBP vendors will need to discuss how they intend to deal with the No Surprises legislation, sooner rather than later.

Financing plans with reference-based pricing have grown in popularity over the last decade. However, as RBP has become more prevalent in the industry, hospital systems have become more knowledgeable about it, and at times, have refused payment entirely from RBP plans, and instead, have opted for immediate balance billing to all plan participants. In response to these provider actions, certain RBP vendors are struggling to produce solutions that will limit disruption to employer and employees while attempting to retain as much of the savings that RBP Plans have been known for. RBP plans generally pay claims at a stated percentage above Medicare (such as 140%, 150%, 200%, etc.), while PPO contracts, although a great savings over non-contracted provider rates, generally result in (if compared to Medicare, which of course their rates are not based on) costs ranging from 300% to 800% of Medicare rates. Sadly, I’ve seen many initial bills from hospitals coming in at over 1,000% of Medicare rates when no network is in place.

“Work-arounds” or “Alternatives” for RBP vendors have included (so far) one-off facility agreements, creating a networked facility, or single case agreements, which is negotiated often-times prior to the participant entering the facility for service. An example is a known procedure or surgery, such as an ACL reconstruction, hip replacement or other procedure. In these cases, some RBP vendors have opted to offer pre-payment to the facility, to encourage them to accept the patient at the RBP rate. There is concern, however, that such pre-negotiated rates could be perceived as a contracted rate, and may set precedents. One of the administrative concerns of this type of solution is the burden that would likely result from pre-negotiations, as well as a possible delay in service while negotiations are in the works.

Another work-around may be direct provider contracts, but those may likely be limited to certain services only, and if providers result in providing additional services, they could opt to balance-bill for those additional services, which may or may not be prohibited under the No Surprises Act, depending on the type of service.

It is assumed by most in the self-insured industry that work with RBP plans that the level of payment for RBP plans may end up increasing to a higher percentage, to still provide savings over PPO plans, but not at the wide difference we are seeing currently. Many of us are expecting payment levels to raise from the 140%-200% rate to perhaps raise to something more like perhaps 200% to 250% for normal facility payments, to cut back on the provider pushback and possible refusal to accept patients under RBP plans.

Before the new September 30, 2021 IDR rules Part 2 were released, I asked two RBP vendors I work with about how they intend to deal with the No Surprises Act. When asked how HS Technologies, an RBP vendor based in Orange County, California, will adjust, President Ryan Day responded as follows: “The No Surprises Act impacts reference-based pricing programs with no facility network. The Interim Final Rule published in July specifically mentions these types of plans in the context of indemnity plans, acknowledging that the scope is limited to emergency facility and professional claims. If there is no facility network associated with a plan, there can’t be a scenario where a member is surprised by receiving services at an in-network facility from an out-of-network provider. This limited scope doesn’t apply when there are one-off agreements with a facility. Our reading of the rule made clear that these agreements would now make it a surprise bill if a member receives out-of-network care at a facility that has such an agreement.”

Ryan Day continued with additional solutions. “HST will be able to identify these surprise bill scenarios and, when the plan includes access to a MultiPlan network, ensure the plan administrator has the network QPA needed to determine the member’s cost share.” HST is now part of Multiplan, with contracted national networks such as PHCS and MultiPlan.

I asked the same question of Larry Thompson, Chief Revenue & Strategy Officer for AMPS, another RBP vendor. Larry stated: “There are many pieces to this. Our Chief Legal Counsel is working on a White Paper to address all of this, and I will provide it once it is complete. In the interim, here are few things to consider. The Act does not specifically target RBP or repricing. While it does address OON, we are prepared to assist our clients who use us for this service. More to follow from our CLO.”

I also asked Ryan Day how they propose to bridge the gap if/when facilities refuse to accept payment entirely from RBP plans? Ryan replied: “HST has routinely experienced a 98% acceptance rate from providers, recognizing not only the fair reimbursement we generate, but also the benefits we can bring to high-accepting facilities. Our HST Connect application helps to steer plan members to those providers, delivering the steerage benefits they typically only expect from network participation. We also engage the provider at key points before service is rendered,

to ensure they understand the plan benefits. Should the facility disagree with the reimbursement, our PAC program and settlement portal make it efficient for the provider to engage in the negotiation now required by the No Surprises Act. Any subsequent arbitration resulting from an inability to reach agreement will leverage the analytic and arbitration support services of MultiPlan to help our employers present the best case.”

Larry Thompson, when asked the same question, responded as follows: “Rarely does this happen – less than 1% of our members ever face this problem. When they do, our advocates work with the facility to explain how our program works, and in the majority of the cases, access is allowed. Failing that, we offer single case agreements so that the facility will allow service. Barring that, we can revert to safe harbor contracts we have in AMPS America, or redirect the service to another facility.”

I also asked Larry how the RBP vendor will coordinate these efforts with the TPA? “Our TPA’s are the first line of contact for most members and providers,” responded Larry. “Through our integration the TPA will know when to transfer members to our Advocacy or Care Navigation teams to resolve any issues with providers.”

Lastly, I asked Ryan Day what types of plan changes/provisions they are recommending plans that are using reference-based pricing add to their plan documents specifically related to the No Surprises Act? “We are considering adjusting the negotiation corridor to allow for settlement

above the typical level for surprise bills specifically ER claims. We are also looking at changing the default reimbursement for ER claims that are impacted by the No Surprises Act.”

As stated in my last article, the IDR process will use a “Baseball-Style” Arbitration process, meaning that the CIDRE is required to pick one of the two “offers” which is closest to the QPA.

Federal vs. State Balance Billing Laws

It is important to note that the No Surprises Act is not intended to displace any state balance billing laws. The issue of state vs. federal law is quite complex and I suggest you seek the advice of legal counsel on this. I will attempt to summarize just the basics of the interaction, but again, this is only a brief summary. The Interim Final Rules defer to existing state requirements with respect to state laws and states that have an established process in place to resolve payment disputes and allow for arbitration. Self-funded plans have the option to opt into a state law where payment standards of the state are expanded, with full protection against balance billing.

Existing federal law says that the out-of-network provider must have a patient sign a consent to receive non-emergency services, but the sate law might prohibit an individual from providing consent to be balance-billed. If a state develops model language that is consistent with the No Surprises Act, HHS will consider a provider or facility that makes appropriate use of the state-developed model language to be compliant with the federal requirement. Again, this is quite complex. I asked Marilyn Monahan if she could comment on the state of California’s balance billing laws and how they will interrelate with the No Surprises Act… “Existing state limits on balance billing – and California has some – will remain in effect for fully insured plans, to the extent that they provide participants with greater rights than they are entitled to under the CAA.”

Enforcement

Enforcement of the No Surprises Act is similar to that of the Affordable Care Act. If a fully insured plan sponsor contracts with a third party, then the third party will be responsible for compliance. In a self-funded health plan, the employer plan sponsor will be responsible for compliance, even if they contract with a third party, such as a TPA, to assist them with providing all of the necessary requirements. The Department of Labor will regulate self-funded plans, and fully insured plans

will be regulated by the states.

As of now, it is stated that up to 25 health plan audits per year will be performed to ensure compliance with the Act, starting in 2022. If, however, the Departments should receive a consumer complaint, they can audit that consumer’s health plan.

Complaints

The No Surprises Act requires the Departments to establish a process for receiving complaints regarding potential violations of the law by providers and insurers. They announced their intention to create one system to intake all complaints related to the various components of the law and direct them to the various departments. The IFR clarifies that there will be no time-limit on complaint filing, but the relevant departments must respond in writing no later than 60 business days after a complaint is received. The regulations contained within the IFR are set to be effective on September 13, 2021, which is 60 days after its publication in the Federal Register.

Next Steps & Conclusion

If you’re feeling stressed over these rules, or if just reading them is making you have that tunnel vision I mentioned in the beginning of Part 1, or if you’re employer dealing with HR issues like the one I described in my example with Judy and Pam, remember to breathe, and remember, the goal of this legislation is to help people and prevent surprise billing practices. Anything new is often confusing and frustrating. Just take one step at a time and keep an eye out for the anticipated end game. Won’t it be nice to one day soon not have to listen to the anxiety in your family member or your clients’ voices and angst in their eyes when they tell you they’ve received an unexpected, surprise medical bill? The No Surprises Act won’t help in every case, but it should help the majority of cases in which surprise medical bills show up in our mailboxes. Personally, I’m hoping they expand the No Surprises Act (or offer something similar) to cover other provider bills not covered under this legislation.

The No Surprises Act’s limitation on balance billing for services provided in an “in-network” facility by an out-of-network provider is likely to be quite problematic for self-funded plans that use Reference-Based Pricing as their financing method, in place of a PPO network.

Helpful Links

If you need/want additional information, you can visit the following links to assist you…

Interim Final Rule and Comment Period: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-9909-ifc-surprise-billing-disclaimer-50.pdf Federal Register: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/13/2021-14379/requirements-related-to-surprise-billing-part-i

CMS Fact Sheets: https://www. cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/requirements-related-surprise-billing-part-i-interim-final-rule-comment-period

Author’s Note: I’d like to thank Marilyn Monahan, Ryan Day, Larry Thompson, Chris Condeluci, Ryan Work and Colleen Dempewolf for their assistance with this article. I’d also like to thank NAHU for the informative webinar in July, which started me on the path to fully research this topic.

DOROTHY COCIU is the Vice President, Communications for the California Association of Health Underwriters and the President of Advanced Benefit Consulting & Insurance Services, Inc., Anaheim, CA. She also hosts the Benefits Executive Roundtable Podcast series on many important educational topics. Other educational articles, educational classes and important information can be found on her company’s website at www.advancedbenefitconsulting. com. She can be reached at dmcociu@advancedbenefitconsulting.com. Educational classes can be found on her educational platform, the Empowered Education Center, at https://advancedbenefitconsulting.com/empowered-education-center/. Her weekly podcast series, Benefits Executive Roundtable, can be found on Spotify, Stitcher, ITunes/Apple Podcasts or Google Podcasts, or at https://advancedbenefitconsulting. com/benefits-executive-roundtable-podcast/.